It’s been some time since my post on the different types of kimono but I really wanted to write a follow-up post to further explore the variations in kimono. Since I covered the different levels of formality kimonos can have in the first post, I thought I’d focus a bit more on how kimonos come about, their relationship to the seasons, and a bit about obi in this post.

How kimono fabric is made

While some types of kimono are made of a single colour (e.g. iromuji), most kimonos are patterned. There are two main ways that patterns can be created on the cloth – through dyeing (染め; some) and weaving (織り; ori)

Types of 染め (Dyed) Kimonos

Some (soh-meh), or dyed kimonos, are pretty straightforward, with the patterns of the kimono being dyed onto a piece of white cloth. Because the cloth remains soft to touch, these kimonos are also called「柔らかもの」(yawaraka mono; soft things). And because the cloth moves with your body, these kimonos give off an elegant vibe. It’s pretty popular for formal kimonos to be dyed, and dyed kimonos can be further divided into these subgroups:

- 手書き友禅 (Tegaki Yuuzen): One of the most famous/representative styles of dyeing, the Tegaki Yuuzen was created by Miyazaki Yuuzensai in Kyoto between the years 168801704. Because glue is used to draw the patterns on, the dyes for different parts of the pattern will not mix.

- 型染め (Katazome): This refers to clothes that have been dyed using stencils (型紙; katagami – lit ‘paper pattern’). Although the history of the technique dates back to the Heian period, it started being used for the bushi in the Edo period and became popular technique.

- ぼがし染め (Bogashizome): This brush-dyeing technique dates back to the Heian period and is known for producing an ombre-pattern.

- 疋田糊置き (Hittanorioki): This is also called 染め疋田 (somehitta) and 糊疋田 (norihitta), this technique uses glue to bring out a shiborizome effect.

- 絞り染め (Shiborizome): This is a sort of tie-dying technique, where you fold and stitch the cloth in a particular way to create a pattern after dyeing.

Types of 織り (Woven) kimonos

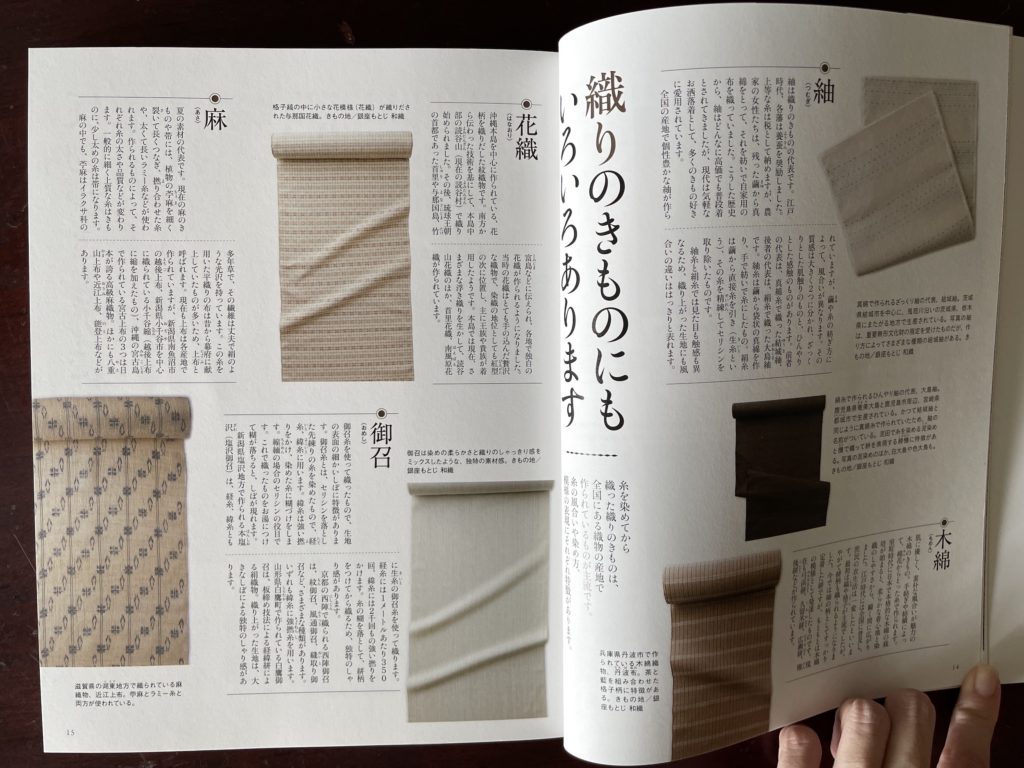

In contrast to dyed kimonos, Ori (oh-ri), or woven kimonos are created with white threads that have been twisted together and then dyed and then woven into a pattern. Because the texture of these fabrics is a bit harder, they are sometimes called「かたもの」(katamono; hard things) or「かたいきもの」(katai kimono, hard kimono). Popular examples of woven kimono would be tsumugi, omeshi, and other casual types of kimono made of cotton. Here are the main subgroups of woven kimonos:

- 紬 (Tsumugi): This is the representative woven kimono technique. During the Edo period, sericulture (producing silk by raising silkworms) was promoted. After the best threads were taken as text, the women would take the left over threads (真綿; mawata) to make cloth for everyday wear. Nowadays, tsumugi kimonos are seen accessible causual chic wear. Yuuki Tsumugi is probably the most famous example of tsumugi cloth.

- 木綿 (Momen): Cotton was introduced to Japan during the Muromachi period and quickly became adopted as a kimono fabric. Popular moment patterns include stripes (縞; shima) and checks/lattic (格子; koushi)

- 花織 (Hanaori): As the name suggests, the Hanaori weaves flower-patterns into the cloth. The base of this technique came to Okinawa from the south and was developed in Yomitanzan (now Yomitan village) before being spread to other parts of Okinawa such as Shuri, Yonagunijima, Taketomijima, etc

- 御召 (Omeshi): Made with omeshi thread (apparently a type of silk thread that does not have sericin), omeshi kimonos are known for their fine-grained texture (細かいしぼ). The two main centres of production for omeshi are Shiozawa in Niigata and Nishijin in Kyoto.

- 麻 (Asa): A popular fabric for the hot summer seasons, modern asa kimonos are made from the ramie plant. While asa is made throughout Japan, the best quality Asa can be found in Uonuma (Niigata), Ojiya (Niigata), and Miyakojima (Okinawa).

A note on Obi

Obi patterns can be made via weaving or dyeing, much like the kimono robes. However, while dyed kimonos tend to be used to make formal and semi-formal kimonos and woven kimonos tend to be for casual occasions, the reverse is true for obi. Woven obi tends to be used for formal and semi-formal occasions (one exception is the Hakata-style woven obi, which is for casual kimonos), dyed obis tend to be used for dressier casual kimonos (e.g. for going out with friends, rather than formal or semi-formal occasions).

Kimono through the Seasons.

I’ve been writing mainly about the types of kimono and the materials they could be made with, but now, it’s time to consider the impact of seasons on the kimono. A kimono suitable for a formal event in winter, for example, would probably be too hot for a formal event held in the peak of summer.

We’ve hinted at the seasonality of the kimono when talking about the Yukata (which is worn almost exclusively in summer), and in fact, it’s traditional to change your kimono wardrobe according to the season. This practice is called 衣替え(koromogae) and generally, you’ll change your wardrobe twice a year.

The practice of koromogae dates back to the Heian period, but in the modern-day, koromogae takes place on 1st June and 1st October. Between October to May, Awase (袷) kimono is to be worn, and from June to September, Hitoe (単衣) is worn. In the height of summer, between July and August, you also have the option of wearing Usumono (薄物). Confused about all these new types of kimono? It’s actually pretty simple:

- Awase kimono has a lining, making it suitable for colder weather.

- Hitoe kimono does not have a lining, making it suitable for warmer weather, but is opaque

- Usumono kimono does not have a lining, but it’s also slightly translucent, making it suitable only for the hottest months.

Tip/my experience: When I bought my first kimono, I bought it in the awase style because in Japan, awase kimonos have a longer period in which they could be worn. However, after moving back to Singapore, I’ve realised that awase kimonos are a bit too thick for our perpetual summer weather! So if you’re buying a kimono, do consider the temperature you’re most likely to wear it as well.

Obi

Types of Obi

I have been neglecting the obi so far, so before I end this post, I want to do a quick introduction of the three most common types of obi.

Fukuro-Obi (袋帯): The most formal type of obi, the fukuro-obi is also the widest and longest, measuring 31cm across. This obi is also the most difficult to put on, given that the obi has no taper.

Nagoya-Obi (名古屋帯): One of the most widely used obi, the Nagoya-obi was created during the Taisho era by a teacher in an all-girls school to make wearing the obi easier. The Nagoya-obi is partially folded in half before it opens up to its full width (similar to the Fukuro obi). At its widest end, the width of the nagoya-obi is the same as the fukuro-obi.

Hanhaba-Obi (半幅帯): The thinnest obi, the Hanhaba-obi is easily recognisable because it looks like it’s folded in half. These obis tend to be 15~17cm in width.

Formal and Informal Obi

I personally find differentiating between formal and informal obi to be difficult because it’s dependent on the pattern of the obi. For formal occasions, you should be pairing your kimono with a fukuro-obi that has gold, silver, or white threads. Basically, something that looks very luxurious. For semi-formal occasions, you could use either the fukuro or nagoya-obi, but the obi should still be a luxurious pattern that uses a lot of gold, silver, and white.

Likewise, the fukuro and nagoya-obi can be used for more casual occasions (although for ease of wear, you’ll probably want to use the nagoya-obi). However, the patterns on these obis should avoid gold, silver, and white – you can have some, but it shouldn’t be the main colour palate. The hanhaba-obi is the most casual of the three obis and should be reserved for the yukata and casual kimonos like the komon. Because of this, a hanhaba-obi with a casual kimono (e.g. komon) is going to come across as more casual than a nagoya-obi with a casual kimono.

Concluding Words

I hope this post helped you understand more about the variations within the kimono, and that the tailoring/seasonality of the kimono makes a huge difference too. If you’ve found these two posts helpful, please consider buying me a tea via ko-fi.

I had no clue about how many differences there were in types of Kimono!

It was really fascinating to learn more!