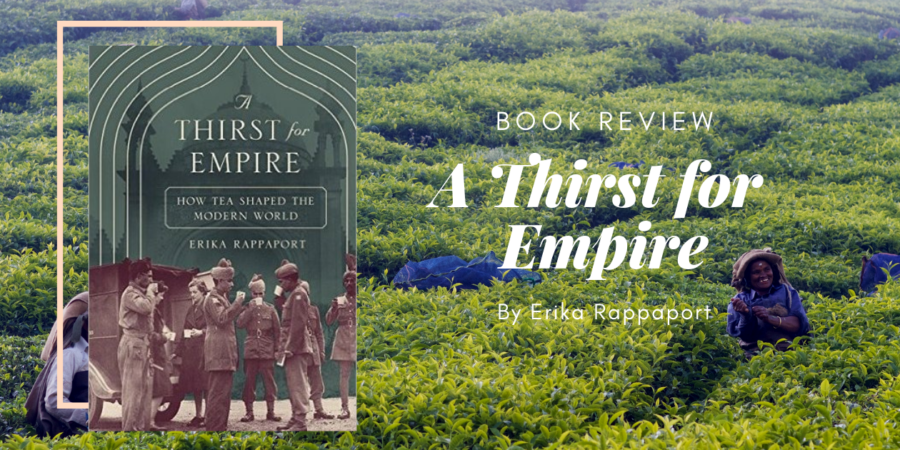

I first heard about this book from NPR’s article “From Raucous To Ritzy: A Brief History Of Christmas Tea” (would recommend this if you want to know about more about how Christmas tea came about!). The book sounded interesting and since the NLB had it, I decided to borrow it.

Unfortunately, I didn’t realise how thick and academic this would be. It took me quite a few days just to read through the whole thing once, and then I had to go through it a second time to make sure I roughly understood what it said. Or perhaps this is just an indication of how rusty my brain has gotten.

Although this book is subtitled “how tea shaped the modern world”, it really is very much focused on the British empire. America, China, and India are fairly extensively discussed, but my impression is that this is only in relation to Britain and the British tea industry.

As you’re probably aware, tea is from China but for some reason, it’s also seen as a very British drink (in particular, black tea). This book traces the journey of tea as its status changes from foreign import to a symbol of Britishness, going into things like how the taste for tea was created, how this influenced Imperial Britain, and even the role of tea in the Great Depression and World War II.

I talked about parts of the book in more detail in my previous posts on Tea and Temperance and the history of Fake Tea, but another thing I learned from this book was how the British moved from Chinese to Indian teas. I had always thought that Robert Fortune’s discovery of tea adulteration was the main cause of the shift to black, Indian teas, but this book showed me that there was also a concerted effort to promote ‘Imperial’ (Indian) teas. In fact, most consumers didn’t like the taste of Indian teas at first, and some tea shops ended up blending Chinese and Indian teas to make them more palatable!

One more thing that I found interesting was the subtle shift in the image of tea. During the heyday of the British empire, Indian teas were sold as ‘Imperial’ products and that consumers would be helping the empire by buying them. However, “by the late 1930s, it was no longer clear that empire added value. Instead, health and bodily renewal became watchwords of the day, shaping advertising and many other facets of European culture.” What this means is that tea was introduced as a healthy Chinese drink, and then through a series of marketing campaigns marketed as a British product, and then when that failed, went back to being a healthy drink that would revive you. In a way, it’s come full circle (but then again, really not since the British public didn’t go back to drinking Chinese teas).

If you’re interested in the history of tea and how it relates to Britan and the British empire, I think you’d really enjoy this book. It’s fairly dry in tone but it has so much information crammed into it that after reading it a couple of times, I think you’ll find that your view of tea has been changed.